How Do.yoi Change Who Can See Your Future

On This Page

- Increasing greenhouse gas concentrations will have many effects

- Future temperature changes

- Time to come ice, snowpack, and permafrost

- Futurity sea level change

- Futurity precipitation and storm events

- Hereafter ocean acidification

Increasing greenhouse gas concentrations will have many furnishings

Greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere will continue to increase unless the billions of tons of our almanac emissions decrease substantially. Increased concentrations are expected to:

- Increase Globe's average temperature

- Influence the patterns and amounts of precipitation

- Reduce ice and snow cover, likewise as permafrost

- Raise bounding main level

- Increment the acidity of the oceans

- Increment the frequency, intensity, and/or duration of extreme events

- Shift ecosystem characteristics

- Increase threats to human being health

These changes will touch on our food supply, water resources, infrastructure, ecosystems, and even our own wellness.

Future changes volition depend on many factors

- NRCClimate Stabilization Targets increase in greenhouse gas concentrations

- Natural influences on climate (e.g., from volcanic activeness and changes in the sun's intensity) and natural processes within the climate system (e.g., changes in ocean circulation patterns)

Scientists use computer models of the climate organisation to improve sympathise these issues and project time to come climate changes.

Past and present-mean solar day greenhouse gas emissions will affect climate far into the future

Many greenhouse gases stay in the atmosphere for long periods of fourth dimension. As a result, fifty-fifty if emissions stopped increasing, atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations would continue to increase and remain elevated for hundreds of years. Moreover, if we stabilized concentrations and the composition of today's atmosphere remained steady (which would crave a dramatic reduction in current greenhouse gas emissions), surface air temperatures would continue to warm. This is because the oceans, which shop heat, take many decades to fully reply to higher greenhouse gas concentrations. The ocean'south response to higher greenhouse gas concentrations and higher temperatures will continue to impact climate over the next several decades to hundreds of years.[two]

To larn more about greenhouse gases, delight visit the Greenhouse Gas Emissions page and the Greenhouse Consequence section of the Causes of Climate change page.

Considering it is hard to project far-off future emissions and other human factors that influence climate, scientists use a range of scenarios using various assumptions about future economic, social, technological, and environmental conditions.

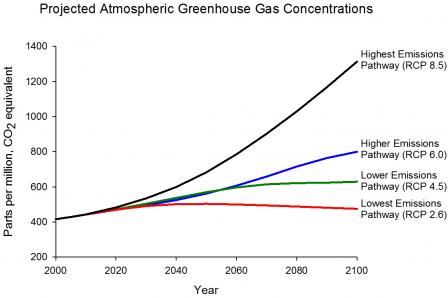

Click the epitome to view a larger version. This figure shows projected greenhouse gas concentrations for iv dissimilar emissions pathways. The superlative pathway assumes that greenhouse gas emissions will proceed to rise throughout the current century. The bottom pathway assumes that emissions reach a peak between 2010 and 2020, failing thereafter.

This figure shows projected greenhouse gas concentrations for iv dissimilar emissions pathways. The superlative pathway assumes that greenhouse gas emissions will proceed to rise throughout the current century. The bottom pathway assumes that emissions reach a peak between 2010 and 2020, failing thereafter.

Source: Graph created from information in the Representative Concentration Pathways Database (Version 2.0.v) http://world wide web.iiasa.air conditioning.at/web-apps/tnt/RcpDb

Acme of Page

Futurity temperature changes

We have already observed global warming over the last several decades. Time to come temperatures are expected to change further. Climate models projection the following key temperature-related changes.

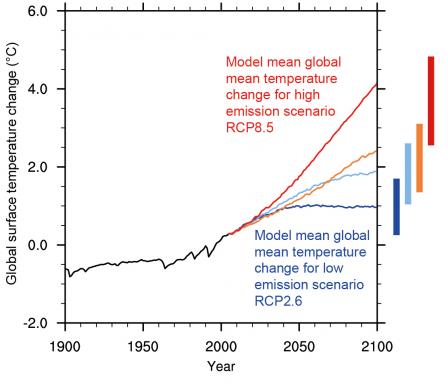

Key global projections

- Increases in average global temperatures are expected to be within the range of 0.5°F to 8.6°F past 2100, with a likely increase of at to the lowest degree 2.7°F for all scenarios except the one representing the most aggressive mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions.[ii]

- Except under the near ambitious mitigation scenario studied, global boilerplate temperature is expected to warm at least twice as much in the side by side 100 years as it has during the terminal 100 years.[two]

- Ground-level air temperatures are expected to go along to warm more rapidly over country than oceans.[2]

- Some parts of the world are projected to see larger temperature increases than the global average.[2]

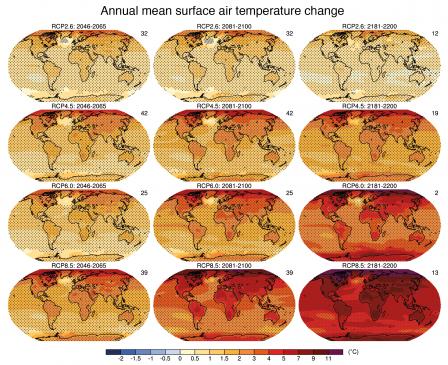

Click the image to view a larger version. Projected changes in global average temperatures under iv emissions pathways (rows) for three different fourth dimension periods (columns). Changes in temperatures are relative to 1986-2005 averages. The pathways come from the IPCC 5th Assessment Study: RCP2.6 is a very low emissions pathway, RCP4.5 is a medium emissions pathway, RCP6.0 is a medium-high emissions pathway, and RCP8.5 is the high emissions pathway (emissions are assumed to continue increasing throughout the century). Source: IPCC, 2013 Go out

Projected changes in global average temperatures under iv emissions pathways (rows) for three different fourth dimension periods (columns). Changes in temperatures are relative to 1986-2005 averages. The pathways come from the IPCC 5th Assessment Study: RCP2.6 is a very low emissions pathway, RCP4.5 is a medium emissions pathway, RCP6.0 is a medium-high emissions pathway, and RCP8.5 is the high emissions pathway (emissions are assumed to continue increasing throughout the century). Source: IPCC, 2013 Go out

Click the paradigm to view a larger version. Observed and projected changes in global average temperature under four emissions pathways. The vertical bars at right prove likely ranges in temperature by the end of the century, while the lines bear witness projections averaged across a range of climate models. Changes are relative to the 1986-2005 average. Source: IPCC, 2013 Exit, FAQ 12.1, Figure i.

Observed and projected changes in global average temperature under four emissions pathways. The vertical bars at right prove likely ranges in temperature by the end of the century, while the lines bear witness projections averaged across a range of climate models. Changes are relative to the 1986-2005 average. Source: IPCC, 2013 Exit, FAQ 12.1, Figure i.

Key U.Southward. projections

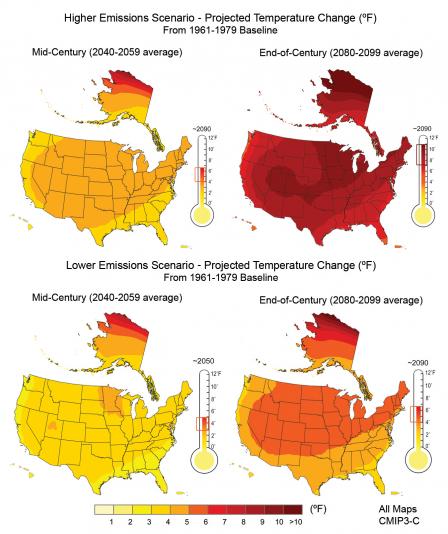

- Past 2100, the average U.S. temperature is projected to increase past about 3°F to 12°F, depending on emissions scenario and climate model.[one]

- An increase in average temperatures worldwide implies more frequent and intense farthermost oestrus events, or estrus waves. The number of days with high temperatures in a higher place 90°F is expected to increase throughout the United states, especially toward the end of the century.[i] Climate models project that if global emissions of greenhouse gases go along to grow, summertime temperatures in the United States that ranked amid the hottest five% in 1950-1979 will occur at to the lowest degree lxx% of the time by 2035-2064.[1]

Projected temperature change for mid-century (left) and end-of-century (correct) in the United states of america under college (top) and lower (bottom) emissions scenarios. The brackets on the thermometers correspond the likely range of model projections, though lower or college outcomes are possible. Source: USGCRP (2009)

Projected temperature change for mid-century (left) and end-of-century (correct) in the United states of america under college (top) and lower (bottom) emissions scenarios. The brackets on the thermometers correspond the likely range of model projections, though lower or college outcomes are possible. Source: USGCRP (2009)

Elevation of Page

Time to come atmospheric precipitation and tempest events

Patterns of precipitation and tempest events, including both pelting and snowfall are also probable to alter. Even so, some of these changes are less sure than the changes associated with temperature. Projections bear witness that future atmospheric precipitation and storm changes will vary by season and region. Some regions may accept less precipitation, some may have more precipitation, and some may have trivial or no modify. The amount of rain falling in heavy precipitation events is likely to increase in virtually regions, while storm tracks are projected to shift poleward.[two] Climate models project the following precipitation and storm changes.

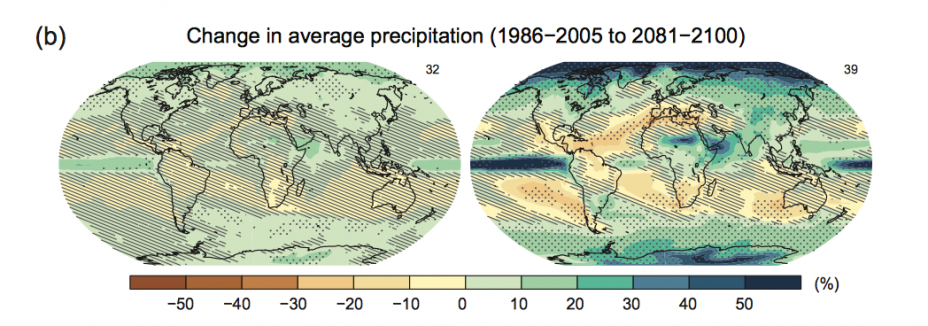

Click the image to view a larger version. Projected changes in global annual hateful precipitation for a low emissions scenario (left) and loftier emissions scenario (right). Bluish and dark-green areas are projected to feel increases in precipitation by the end of the century, while yellowish and dark-brown areas are projected to experience decreases.

Projected changes in global annual hateful precipitation for a low emissions scenario (left) and loftier emissions scenario (right). Bluish and dark-green areas are projected to feel increases in precipitation by the end of the century, while yellowish and dark-brown areas are projected to experience decreases.

Source: IPCC, 2013 Go out

Key global projections

- Global average annual precipitation through the end of the century is expected to increase, although changes in the corporeality and intensity of atmospheric precipitation will vary significantly by region.[ii]

- The intensity of precipitation events volition probable increase on boilerplate. This volition be particularly pronounced in tropical and high-latitude regions, which are also expected to feel overall increases in precipitation.[2]

- The strength of the winds associated with tropical storms is likely to increase. The amount of precipitation falling in tropical storms is also likely to increase.[2]

- Annual average precipitation is projected to increase in some areas and decrease in others. The figure to the right shows projected regional differences in precipitation under two emission scenarios.[2]

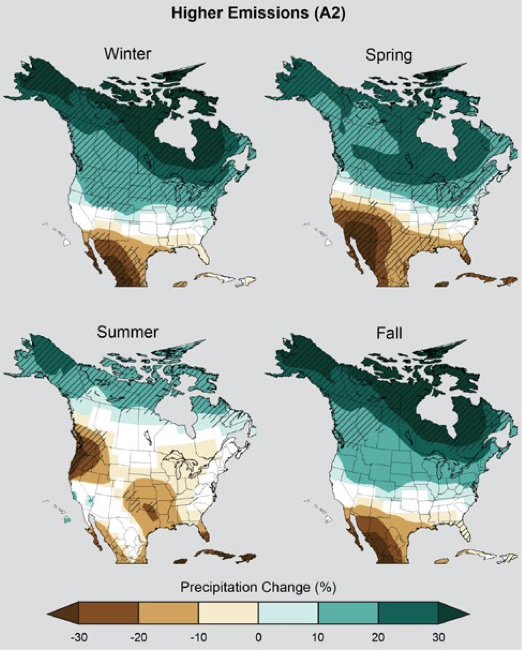

Primal U.S. projections

- Northern areas are projected to get wetter, especially in the winter and spring. Southern areas, especially the Southwest, are projected to become drier.[ane]

- Heavy precipitation events will likely be more frequent, even in areas where full precipitation is projected to decrease. Heavy downpours that currently occur nearly once every 20 years are projected to occur between twice and five times as frequently by 2100, depending on location.[ane]

- The proportion of precipitation falling every bit rain rather than snowfall is expected to increase, except in far northern areas.[1]

- The intensity of Atlantic hurricanes is likely to increase equally the ocean warms. Climate models projection an increase in the number of the strongest (Category 4 and 5) hurricanes, as well as greater rainfall rates in hurricanes.[1]There is less confidence in projections of the frequency of hurricanes.[1]

- Common cold-flavor storm tracks are expected to go on to shift n. The strongest cold-season storms are projected to become stronger and more frequent.[1]

Click the image to view a larger version. The maps show projected future changes in precipitation for the terminate of this century, compared with 1970-1999, under a higher emissions scenario. For case, in wintertime and leap, climate models hold that northern areas in the United States are likely to get wetter and southern areas drier. There is less confidence in exactly where the transition between wetter and drier areas will occur. Confidence in the projected changes is highest in the areas marked with diagonal lines. The changes in white areas are not projected to exist larger than what would be expected from natural variability. Source: U.S. National Climate Assessment, 2014.

The maps show projected future changes in precipitation for the terminate of this century, compared with 1970-1999, under a higher emissions scenario. For case, in wintertime and leap, climate models hold that northern areas in the United States are likely to get wetter and southern areas drier. There is less confidence in exactly where the transition between wetter and drier areas will occur. Confidence in the projected changes is highest in the areas marked with diagonal lines. The changes in white areas are not projected to exist larger than what would be expected from natural variability. Source: U.S. National Climate Assessment, 2014.

Summit of Page

Future water ice, snowpack, and permafrost

Arctic sea water ice is already declining.[2] The area of snow comprehend in the Northern Hemisphere has decreased since about 1970.[2] Permafrost temperatures in Alaska and much of the Arctic[2] have increased over the concluding century.[1] To learn more about recent changes in snowfall and ice, visit the Snowfall and Ice page of the Indicators section.

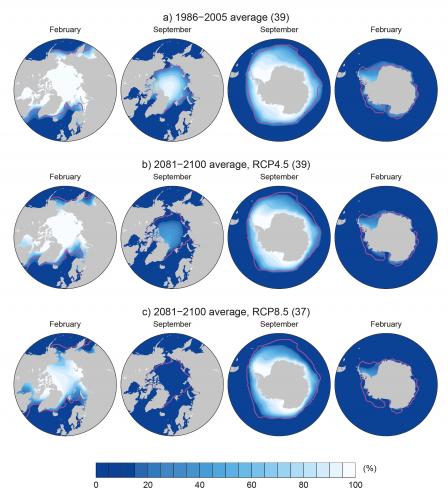

Over the adjacent century, it is expected that bounding main ice volition continue to reject, glaciers will proceed to shrink, snowfall cover will continue to decrease, and permafrost will go along to thaw. Potential changes to ice, snow, and permafrost are described below. Click the paradigm to view a larger version. These maps show projected losses of sea ice in the Arctic and Antarctica. The maps in a) testify the boilerplate ice concentration (the relative area covered by sea water ice) from 1986-2005. The maps in b) and c) testify climate model simulations of sea ice thickness in Feb and September almost the finish of the 21st century nether low (b) and high (c) emission scenarios. In the Arctic, February is projected to have less ice (more blueish); September is projected to be nearly water ice-free (almost all blue). The projected changes in Antarctic ocean ice are more than subtle. Source: IPCC, 2013

These maps show projected losses of sea ice in the Arctic and Antarctica. The maps in a) testify the boilerplate ice concentration (the relative area covered by sea water ice) from 1986-2005. The maps in b) and c) testify climate model simulations of sea ice thickness in Feb and September almost the finish of the 21st century nether low (b) and high (c) emission scenarios. In the Arctic, February is projected to have less ice (more blueish); September is projected to be nearly water ice-free (almost all blue). The projected changes in Antarctic ocean ice are more than subtle. Source: IPCC, 2013

Fundamental global projections

- For every 2°F of warming, models project virtually a xv% decrease in the extent of annually averaged Chill ocean ice and a 25% decrease in the expanse covered by Arctic sea ice at the end of summer (September).[iii] Note that this decrease does non contribute to bounding main level ascent.

- The coastal sections of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are expected to continue to melt or slide into the body of water. If the charge per unit of this ice melting increases in the 21st century, the ice sheets could add significantly to global ocean level rise.[3]

- Glaciers are expected to continue to decrease in size. The rate of melting is expected to continue to increase, which will contribute to sea level rising.[iii]

Central U.S. projections

- Northern Hemisphere snowfall cover is expected to decrease by approximately 15% by 2100.[3]

- Models projection the snow season volition keep to shorten, with snow aggregating beginning subsequently and melting starting before. Snowpack is expected to decrease in many regions.[3]

- Permafrost is expected to continue to thaw in northern latitudes, damaging buildings, infrastructure, and ecosystems in Alaska.[3]

Pinnacle of Page

Time to come sea level change

Meltwater flowing from the Greenland ice sheet Source: NASA Warming temperatures contribute to bounding main level rise by: expanding ocean water; melting mountain glaciers and ice caps; and causing portions of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets to melt or flow into the body of water.[3]

Meltwater flowing from the Greenland ice sheet Source: NASA Warming temperatures contribute to bounding main level rise by: expanding ocean water; melting mountain glaciers and ice caps; and causing portions of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets to melt or flow into the body of water.[3]

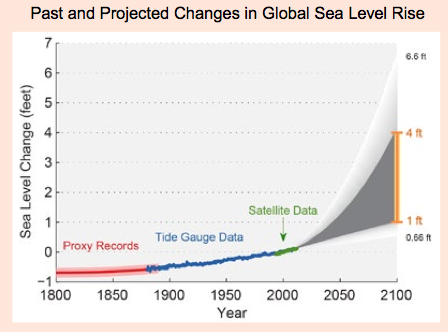

Since 1870, global sea level has risen by near 7.5 inches.[ii] Estimates of time to come ocean level rise vary for different regions, just global sea level for the next century is expected to rise at a greater rate than during the past 50 years.[two]Studies project global sea level to rise by another 1 to four feet past 2100, with an incertitude range of 0.66 to six.6 feet.[one]

The contribution of thermal expansion, ice caps, and small glaciers to sea level rise is relatively well studied, but the impacts of climate change on water ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are less understood and represent an active area of inquiry. Changes in ice sheets are currently expected to account for 1.two to 8 inches of body of water level ascent by the end of this century.[3]

Click the image to view a larger version. Past and projected body of water level rise from 1800 to 2100. The orange line at right shows the currently projected range of sea level rise of 1 to 4 feet past 2100; the wider range (0.66 feet to 6.6 feet) reflects dubiousness near how glaciers and water ice sheets will react to climate change. Source: NCA, 2014.

Past and projected body of water level rise from 1800 to 2100. The orange line at right shows the currently projected range of sea level rise of 1 to 4 feet past 2100; the wider range (0.66 feet to 6.6 feet) reflects dubiousness near how glaciers and water ice sheets will react to climate change. Source: NCA, 2014.

- ii.three feet at New York City

- two.nine anxiety at Hampton Roads, Virginia

- three.five feet at Galveston, Texas

- 1 foot at Neah Bay in Washington state

Relative sea level rise likewise depends on local changes in currents, winds, salinity, and water temperatures, too as proximity to thinning ice sheets.[2]

Top of Page

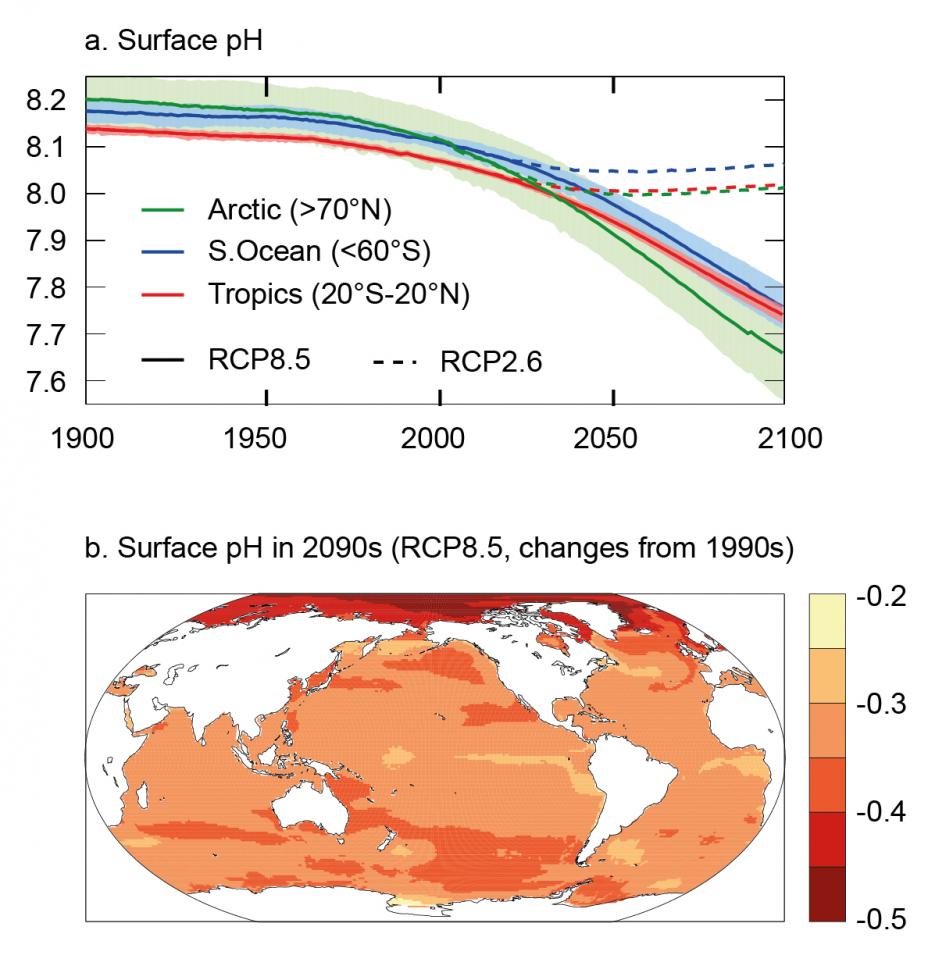

Future body of water acidification

Ocean acidification adversely affects many marine species, including plankton, mollusks, shellfish, and corals. As body of water acidification increases, the availability of calcium carbonate volition reject. Calcium carbonate is a cardinal building cake for the shells and skeletons of many marine organisms. If atmospheric CO2 concentrations double, coral calcification rates are projected to decline by more than 30%. If COtwo concentrations keep to rise at their current rate, the combination of climate warming and ocean acidification could deadening coral growth by nearly l% by 2050.[5]

Click the image to view a larger version. Oceans become more acidic every bit carbon dioxide (COtwo) emissions in the temper deliquesce in the ocean. This modify is measured on the pH calibration, with lower values beingness more acidic. The pH level of the oceans has decreased by approximately 0.one pH units since pre-industrial times, which is equivalent to an approximately 30% increase in acerbity. As shown in the graph and map in a higher place, the pH level of the oceans is projected to decrease even more by the end of the century as COii concentrations are expected to increment for the foreseeable future.[1] [2]Source: IPCC, 2013, Chapter 6.

Oceans become more acidic every bit carbon dioxide (COtwo) emissions in the temper deliquesce in the ocean. This modify is measured on the pH calibration, with lower values beingness more acidic. The pH level of the oceans has decreased by approximately 0.one pH units since pre-industrial times, which is equivalent to an approximately 30% increase in acerbity. As shown in the graph and map in a higher place, the pH level of the oceans is projected to decrease even more by the end of the century as COii concentrations are expected to increment for the foreseeable future.[1] [2]Source: IPCC, 2013, Chapter 6.

Elevation of Folio

References

[one] USGCRP (2014) Melillo, Jerry Yard., Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and Gary W. Yohe, Eds., 2014:Climate Modify Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment. U.Southward. Global Change Research Program.

[ii] IPCC (2013).Climate change 2013: The Physical Science BasisLeave. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Written report of the Intergovernmental Console on Climatic change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, Yard.-Yard. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge Academy Printing, Cambridge, U.k. and New York, NY, Us.

[three] NRC (2011).Climate Stabilization Targets: Emissions, Concentrations, and Impacts over Decades to MillenniaExit. National Research Council. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, Us.

[4] USGCRP (2009).Global Climatic change Impacts in the Us. Thomas R. Karl, Jerry Yard. Melillo, and Thomas C. Peterson (eds.). The states Global Change Research Program. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, U.s..

[v] IPCC (2014). Climatic change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability.

Meridian of Page

How Do.yoi Change Who Can See Your Future,

Source: https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/climate-change-science/future-climate-change_.html

Posted by: overstreethaterequed.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Do.yoi Change Who Can See Your Future"

Post a Comment